The Satellite Hack Everyone Is Finally Talking About

As Putin began his invasion of Ukraine, a network used throughout Europe—and by the Ukrainian military—faced an unprecedented cyberattack that doubled as an industrywide wake-up call.

Andreas Wickberg loves snowmobiling to the house he built in the icy reaches of Lapland, north of the Arctic Circle. Each month come spring, he and his wife relocate for a week or so to a “very, very isolated” spot about 335 miles northwest of their usual home near Umea, a Swedish university town. Up in Lapland, it’s just them and three other houses. Wickberg develops payment-processing software for a Swedish e-commerce company. What makes this possible is satellite internet: For 500 krona ($45) a month, he and his wife can make work calls by day and stream movies by night.

Just over a year ago, though, they and their neighbors found themselves cut off from the outside world. At 7 a.m. on Feb. 24, 2022, Wickberg turned on his computer and took in the news that Russian President Vladimir Putin had begun an invasion of Ukraine with airstrikes on Kyiv and many other cities. Wickberg read everything he could, aghast. Not long after, a neighbor came around asking to borrow the family’s Wi-Fi password because their internet was on the fritz. Wickberg obliged, but 10 minutes later, his connection dropped, too. When he checked his modem, all four lights were off, meaning the device was no longer communicating with KA-SAT, Viasat Inc.’s 13,560-pound satellite floating 22,236 miles above.

Courtesy Airbus

The way each of the connections in his community switched off one by one left him convinced that this wasn’t just a glitch. He concluded Russia had hacked his modem. “It’s a scary feeling,” Wickberg says. “I actually thought that these systems were much more secure, that it was sort of far-fetched that this could even happen.”

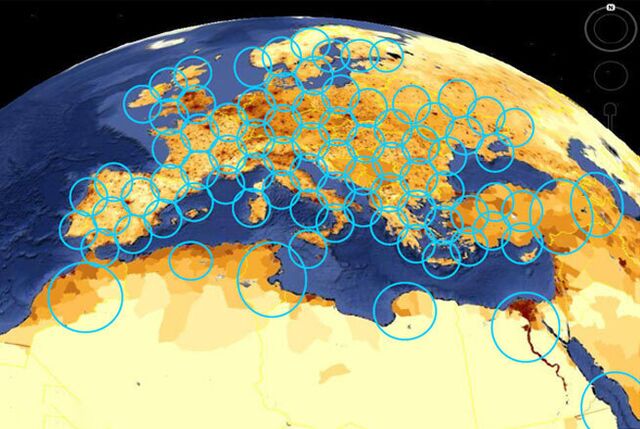

Viasat staffers in the US, where the company is based, were caught by surprise, too. Across Europe and North Africa, tens of thousands of internet connections in at least 13 countries were going dead. Some of the biggest service disruptions affected providers Bigblu Broadband Plc in the UK and NordNet AB in France, as well as utility systems that monitor thousands of wind turbines in Germany. The most critical affected Ukraine: Several thousand satellite systems that President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s government depended on were all down, making it much tougher for the military and intelligence services to coordinate troop and drone movements in the hours after the invasion.

Alerts from customers, engineers and automated systems soon began to flood in via phone, Slack and email, according to a senior Viasat executive who was part of the response team and spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. Attackers were overwhelming the customers’ modems with a barrage of malicious traffic and other kinds of attacks. It took Viasat hours solely to stabilize most of its network, and the official says it then spent many weeks fending off subsequent attacks of “increasing intensity.”

It would take 35 days for Viasat to even begin to say publicly what it thought had happened, and 75 days for any country to point the finger officially at Russia. In the meantime, Ukrainian officials trying to reach remote locations were forced to rely where they could on landlines, cellphones, even dispatching runners to reach the front lines. “Industry was caught flat-footed,” says Gregory Falco, a space cybersecurity expert who has advised the US government. “Ukrainians paid the price.”

While Zelenskiy and his deputies have mostly declined to discuss the hack’s impact on their operations, Viktor Zhora, a senior Ukrainian cybersecurity official, told reporters last year that it resulted in “a really huge loss in communications.” The Russian Embassy in Washington denies any responsibility for the attack, dismissing blame as “detached from reality.”

Space ISAC

The attack was, however, a wake-up call. “The war is really just revealing the capabilities,” says Erin Miller, who runs the Space Information Sharing and Analysis Center, a trade group that gathers data on orbital threats. Cyberattacks affecting the industry, she says, have become a daily occurrence. The Viasat hack was widely considered a harbinger of attacks to come.

Just about every day, more people around the world rely on satellite internet connections than did the day before. Yet for decades, industry specialists say, the commercial satellite industry has underinvested in security measures and essentially ignored what might happen if its systems were hacked on a grand scale. There are 5,000 active satellites circling the planet, and high-end estimates predict the number will top 100,000 by the end of the decade. While smaller, cheaper satellites are being launched into orbit by the thousands, the machines and the networks that run them remain woefully insecure. Customers who rely on them need a backup plan.

For decades after the dawn of the Space Age, nobody worried much about making satellites tamper-proof—it was tough enough just to put them in orbit. By the 1980s, though, there were more sat systems to play with, and spies and amateurs alike started figuring out how to do it. In 1986, John MacDougall, an American engineer who dubbed himself Captain Midnight, jammed HBO’s signal to protest fee hikes. Today, China, Russia, the US and dozens of other nations have demonstrated that they can hack stuff in space, according to James Pavur, a cybersecurity researcher who recently went to work for the Pentagon as a digital service expert. His research has shown just how easy it is to hack an orbiting satellite, its data transmissions or the ground networks that support them.

● Signal hijacking

In 1986, John MacDougall, an American engineer who dubbed himself Captain Midnight, hijacked HBO’s satellite television signal to protest fee hikes. He broadcast his complaint for four minutes.Courtesy YouTube

Almost all of daily life entails some use of satellites. GPS coordinates and space-based relays are an essential component not only of global communications, military operations and weather forecasting, but also of farms, power grids, transportation networks, ATMs and some digital clocks. All 16 infrastructure sectors the US has designated as critical “depend to a great extent, pretty much all of them, on space systems,” says Sam Visner, a former chief of the National Security Agency’s Signals Intelligence programs who’s now vice chair of the Space ISAC. Visner has argued for years that satellite systems aren’t secure enough, including the ground stations. Pavur says this gear has been hacked at least two dozen times in the past decade or so. As part of his 2019 doctoral thesis at the University of Oxford, he intercepted sensitive communications beamed down to ships and Fortune 500 companies, including crew manifests, passport details and credit card numbers and payments, all with $400 worth of home equipment. “It turns out to be easy,” he says. “I just bought some cheap antennas, pointed them at some satellites and found I could clean up the data from the signals, because nothing is encrypted.”

● SSA deception

According to this theory, a devious operator in charge of labeling large fields of orbital debris so satellites can safely avoid them could manipulate Space Situational Awareness (SSA) data to disguise their own spy satellite as a piece of space debris.In the year before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the US intelligence community warned publicly and privately that Russia was testing its ability to hack and destroy satellite systems. Even so, it remained easy for companies to underestimate the risks—partly because there were so many new intermediaries between them and end users, and partly because space still seemed untouchable. Denial was the norm, allowing businesses to save on infrastructure spending while leaving no single company more responsible than another for a potential catastrophe.

A month before the modems went dead, the NSA issued a warning about multiple vulnerabilities in commercial satellite equipment and recommended a series of security-conscious practices, including encryption, password changes, software updates and steps to keep network management systems isolated from one another. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency also gave classified briefings to industry leaders. President Joe Biden was preparing for the possibility that Russia would invade Ukraine, and he wanted to assess what kinds of cyberattacks Putin might retaliate with if the US imposed economic sanctions, according to a White House official familiar with his thinking, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss national security matters. The official, who says companies need to radically improve the security of satellite ground systems, also says the federal government regularly asks companies privately to patch particular vulnerabilities, and some just don’t.

● Seizure of control

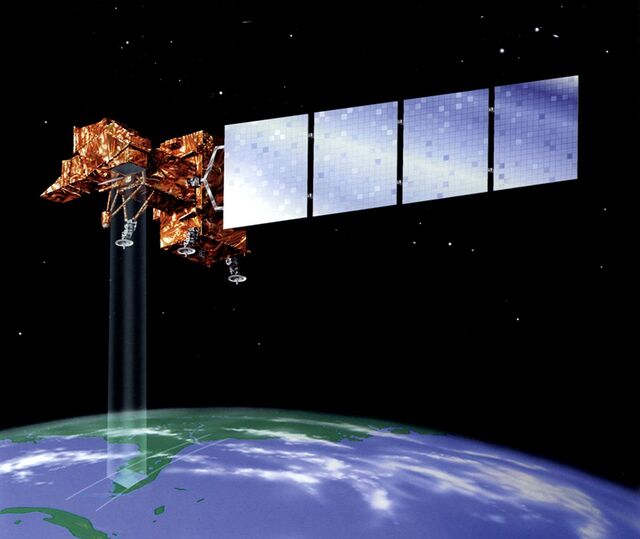

According to US officials, China took direct control of two Earth observation satellites in 2008, including Landsat 7 (above), by first hacking a ground station.NASA

The senior Viasat executive says the NSA’s public warning was too vague to serve as a real heads-up. He says the company discussed it with the agency and concluded it wasn’t specifically relevant to Viasat’s operations, which include beaming Wi-Fi connectivity to sensitive government aircraft. But the NSA cited a 2018 paper by Ruben Santamarta, an independent cybersecurity researcher, that might’ve given the company pause. He’d concluded that flaws in a network’s configuration—the settings that keep it running—could leave military modems hackable.

Santamarta says the critical vulnerability of satellite ground systems was plain as day back in 2014, when he wrote a different paper outlining how an invading military could hack and disable mobile satellite terminals and head off a counterattack. When he presented that one, the industry downplayed the threat. Until last year he’d never seen the attack he’d described in real life, but pages 10 and 11 of the 2014 paper, he says, are “literally what happened in Ukraine.”

● Solar storms

A little over a year ago, a geomagnetic storm triggered by a large burst of radiation from the sun rendered dozens of just-launched SpaceX satellites inoperable.NASA

In the weeks after the attack, Wickberg, who read a blog post Santamarta had written about it, sent the researcher one of the affected modems. Santamarta began pulling the hacked device apart with a screwdriver and a hot air gun, using a special reader to examine its rewritable flash memory. In a normal modem, the code that runs the device appears as a bunch of different numbers and word strings. Instead, Santamarta saw a meaningless pattern—junk data that had wiped the modem clean. “It was basically garbage,” he says. After further review, he concluded the modem could be overwritten without any kind of authentication. In other words, Viasat left a door open.

The same day Santamarta was dissecting the modem, Viasat issued an opaque statement that essentially blamed one of its corporate partners. Viasat had flown afflicted modems to California for its own inspections and reverse-engineered the hack, then traced the wiper malware to a management network server, where it discovered what appeared to be a malware toolkit. A month later, with its broadband service still in disarray, Viasat suggested the hack had taken advantage of an embarrassingly basic hole in a part of the network run by Skylogic SpA. Skylogic was meant to secure the system with virtual private network software. “Subsequent investigation and forensic analysis identified a ground-based network intrusion by an attacker exploiting a misconfiguration in a VPN appliance,” Viasat said in its statement. Mark Dankberg, then the company’s executive chairman, said the attack “was preventable, but we didn’t have that capability.”

● Jamming

Radio signals can be deployed to interfere with satellite data transmissions. Russia has jammed GPS signal receivers in Ukraine, according to US Space Command. Elon Musk has said Starlink terminals near active fighting have also been jammed for hours at a time.Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters

Skylogic’s parent company, the French telecom Eutelsat Communications SA, acknowledges that a VPN in Turin, Italy, where Skylogic is based, was the entry point for the hack, but denies responsibility. It says that the key flaws were in Viasat’s modem equipment, the target of the advanced attack, and that flaws in the user part of the ecosystem were a “well-known fact.” Santamarta says hacking one part of a complex network shouldn’t give you access to all of it. “If a threat actor has access to the management system, it’s almost game over,” he says.

In the wake of the hack, neither company mentioned seeking out the perpetrator or uttered the name Russia. For months, Viasat declined further public comment on the matter, irking US officials, peers and researchers. It simply replaced more than 45,000 affected modems and kept its head down. Privately, Viasat executives joined a classified briefing about the hack that the US intelligence community gave to a range of worried commercial space companies in late March, according to several attendees. Some guests received security clearances for the day. While one attendee says the briefing lacked key details required to put reforms into action, another says it succeeded at one thing: forcing the issue.

Under a Hack

An attacker has lots of ways to get into a satellite internet network. Here’s what happened to Viasat’s KA-SAT, and what didn’t.

By then, US officials had begun telling reporters that Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU, was responsible for the attack. Researchers determined that a piece of malware called ukrop, which had been anonymously uploaded to a public repository in mid-March, was the same wiper used against Viasat. (Ukrop is a Russian slur for Ukrainians but could also be short for “Ukraine operation.”) In the malware’s code, they found similarities to a 2018 virus that the US had attributed to a Russian hacking group with alleged GRU ties.

One of the most significant insights US intelligence gleaned was that the Russians were prepared to take significant diplomatic and strategic risks. They knew spillover from the satellite attack would affect countries outside Ukraine but decided to proceed anyway.

For Anne Neuberger, US deputy national security adviser for cybersecurity and emerging technologies, drawing private conclusions wasn’t enough. She wanted consequences. The US quietly spent six weeks talking allies in the affected area into publicly blaming Russia. That was more complicated than it might sound: As a matter of policy, many countries simply don’t attribute responsibility for cyberattacks to other nations for fear of hurting diplomatic relations or inciting further attacks. (And Washington’s intelligence claims haven’t always proven reliable.) “Attribution is still very uncomfortable to many countries because, at the end of the day, it’s political,” Neuberger says, “but this is also why it is so important.” To make the case, the US Department of State and intelligence agencies shared broad technical information with the European Union and classified intel with France and Germany to overcome the influential members’ initial reluctance, says a European official who’s not authorized to speak publicly.

Eventually, in May, the EU released a strongly worded statement censuring Russia for targeting the KA-SAT network. “This unacceptable cyberattack is yet another example of Russia’s continued pattern of irresponsible behaviour in cyberspace, which also formed an integral part of its illegal and unjustified invasion of Ukraine,” the statement read. The US was careful to point the finger second, and the UK, Canada and Australia joined, too. The American government also sent satellite terminals to Ukraine.

These countries are still dithering over how to improve satellite security for the long term. “There’s not a lot of coordinated action in the US right now,” says Falco, the space cybersecurity expert, who’s part of a new effort to establish global standards. “No one really has the ball.” Much of this comes down to complex supply chains and simple self-interest. Many satellite companies fight regulation, even if it comes with more classified briefings and better intel, because they don’t want to deal with the red tape—or invest in making their systems safer. Viasat, for its part, is among holdouts that haven’t joined the Space ISAC, the info-sharing trade group. (The company says it will join, though it wouldn’t say when.) Over the past year, the group’s 65 members have run a series of tabletop war games modeling responses to similar attacks.

One lesson of the Viasat hack is the need for alternatives to satellite communications. Armies may struggle to stay online if they rely on civilian operators reluctant to go up against military-grade hackers, and the US and its NATO allies have urgently sought backup systems for future conflicts. Elon Musk’s Starlink Inc.—a private network of thousands of tiny satellites, rather than one massive one, like KA-SAT—came to the rescue in Ukraine. But private networks aren’t panaceas. Musk has said Starlink, too, has faced repeated jamming and hack attempts and has also refused to facilitate long-range drone strikes.

In September, the head of the Russian delegation to a United Nations working group on space threats said commercial satellites used to support enemy militaries may also become “a legitimate target for retaliation.” “It seems like our colleagues do not realize that such actions in fact constitute indirect involvement in military conflicts,” diplomat Konstantin Vorontsov told attendees in Geneva. Humanitarian groups seem to be in rare, uncomfortable agreement. The International Committee of the Red Cross said in February that military space systems need to be kept separate from civilian ones.

In the US, the Pentagon’s public efforts to strengthen satellite defenses have centered on Hack-a-Sat, a competition now in its fourth year. It offers a $50,000 grand prize (plus street cred) to teams of researchers who hack simulated satellites and write reports on their tactics and the systems’ vulnerabilities. Teams are scored based on their completion of virtual challenges and their attacks on rivals’ systems. At the next qualifier, in April, 800 teams are expected to compete to commandeer a live satellite in orbit later this year.

Steve Colenzo, a US Air Force computer scientist who helps run the competition, says his team is trying to build trust and lend the military a sense of cool. Speaking against a video backdrop reminiscent of the 1990s movie Hackers, he acknowledges that it’s a leap. The Hack-a-Sat website is daubed in graffiti and has a skull-and-crossbones insignia. “We must do what it takes to secure the universe,” it reads, and build “a global alliance of hackers, researchers and everyday enthusiasts who nerd out on hacking and securing the future of space.”

Viasat says it has actively shared what it can with law enforcement officials and other stakeholders. It shared additional findings with Bloomberg Businessweek, but the details still fall short of explaining how the attackers made their way through the system or targeted particular areas. The company says its caginess owes to its prioritizing security, and stresses that it wasn’t in control of the network that was hacked.

For many in the cybersecurity industry, the most striking thing about the Viasat hack is that, unlike with a phishing attack, there was nothing Wickberg or the Ukrainian military could’ve done to prevent it. “The victim didn’t do anything,” says Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade, senior director of research at SentinelOne, a cybersecurity firm that analyzed the malware. “All you had to do was wake up that morning and drink your coffee and get infected.” Put another way: Satellite connections could start blinking off again at any time. Critical systems can’t fully count on them, nor can people who live a ways off from everyone else.

Since the attack, the broader psychology of denial has begun to dissolve. In March the Space ISAC is due to open a facility in Colorado Springs that aims to keep a more active eye on threats to its members, including hacks, signal jams and other attacks on satellites and their supply chains. A US law passed last year will soon require all critical infrastructure companies to report any significant cyberattacks to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency within 72 hours.

There’s a lot left to do. The satellite services industry remains convoluted and opaque, especially to customers who may have no idea how many intermediaries are involved in their service, according to research by MJ Emanuel, an incident response analyst at CISA. Ground-based parts of the systems, which are generally a mess of connections, networks and third parties, can be especially vulnerable for this reason. Also, it’s tough to fix code in space. Guerrero-Saade, a former national security adviser to the president of Ecuador, says companies at all levels of the industry need to spend less time lobbying and more time improving their security. Governments, he says, need to take a more interventionist stance.

For the companies, the business repercussions of the hack have been minimal. Valued at $469 billion in 2021, the industry has continued growing steadily. Viasat’s business, too, seems to be fine—even though, according to the senior executive, threats against the KA-SAT network are ongoing. Viasat says it has continued to implement changes but wouldn’t describe them. “The Russians had to know quite a bit about Viasat’s system in order to execute this,” Falco says. “It is super, super repeatable.”